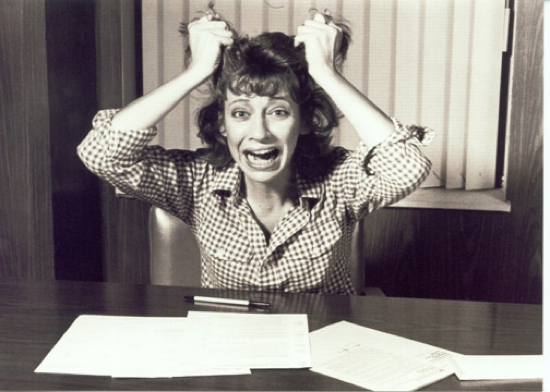

Don’t ask a systems thinker for advice on managing performance or staff engagement. They will probably say something pretty fruity and you’ll wind up frustrated by how fervently they trash conventional wisdom on the subject. Of course performance, engagement, recruitment, they’re all connected, so your systems thinking friend will sound like a fruit loop because they’ll see the whole picture and proceed to suggest that you are asking the wrong questions, when all you wanted to know is “how to get people to do stuff”. You go to them as a sounding board because there is something you like about the way they think; when you’ve talked previously, they come up with ideas that seem counter-intuitive at first, but are actually surprisingly on the money. However, when it comes to a sticky situation you are actually dealing with, you don’t want to hear them bang on about the system, the system, the system. Isn’t that just lovely sounding theories that academics spout? (…wouldn’t work in the real world) In an effort to get them to answer your simple question, you keep repeating “Yes, but they are SUPPOSED to fill out their daily task logs,” quietly tearing your hair out while they insist it’s not a behavioural problem; it’s a systems issue.

One of the most important things I learnt from my past life as a therapist is that if you want behaviour change in an individual, you work with them as a whole being and you work with their whole system (family, friends, peers, environment). You don’t focus on their “problem behaviours”. Similarly, if you want behaviour change in an organisation, you work on it as a whole. You don’t focus on the dysfunctional parts or the underperforming individuals. In my present life as a sociatrist, I apply my understanding of systems to organisations and organisational change, not merely the individuals within them.

We can’t blame individuals for doing what the system expects them to do. As disturbing as Milgram’s experiments were, one thing I observed (and I may be entirely off the mark here) is that people behave in ways which surprise themselves and which sometimes go against what they know to be right and true. We do this when our environment, our system, sets up conditions which compel us to behave in particular ways. The system also punishes us for not doing what it wants us to do, just to keep us in line. We do what we’re told.

What we need if we want organisational transformation, if we want more effective organisations, if we want people to find the work they do meaningful: we need to work with the whole system. A buddy of mine in England recently observed that most people seem uninterested in effectiveness. Sad but true, I fear. Still desperately clinging on to “scientific” management mythologies, many folks just seem to want the numbers to add up and people to do what they’re told. A scary prospect if your business has just appointed a new global CEO who is a bean-counter by background and disposition and whose single-minded purpose is to show the shareholders that they are getting richer every quarter. Calling a performance issue a “behavioural problem” comes out of a mechanistic worldview. Yuck.

There is hope, however. Some managers are on the threshold of doing something quite different….if we would just hang in with them. They know in their gut that doing the same old, same old is not going to make a real difference. I’ve been working with a manager and his two off-siders, all three of whom lead their business. I’ve been coaching them to see the bigger picture and assisting them to open their thinking about why things don’t go the way they’d like. This, to me, is phase one of the organisational transformation they are seeking to effect. Phase one: eliminating systems blindness. Our sessions usually begin with each of them discussing what so-and-so hasn’t done yet again or what what’s-his-name is still doing, despite that one-to-one chat urging them to stop it. I let them get some things off their chest and jot down a few salient things that I pick up. As I listen, I make connections in my head and find the patterns they are describing. These patterns are descriptors of the system. After a little while, I might say something like, “Haven’t we heard all this before?” They smile. Then they frown. What they are slowly learning to do, however, is to see the behaviours as indicators of the wider patterns at play.

The patterns I’m observing in how they describe the staff illustrate a workplace culture characterised by:

- things done at the last minute without much fore-thought

- poor self-discipline with regards working practices

- low self-reponsibility

- poor following up of commitments and promises

- getting easily side-tracked

- being reactive, rather than proactive

- a “she’ll be right” mentality (a common expression in New Zealand meaning, it’ll all be fine in the end, don’t worry about it)

- inconsistency in work practices

- an overly laidback attitude towards work

- a “can’t do” attitude

Behaviours at work are tempered by the systemic norms; you could also say it’s the “culture”. You can read this in many places on the interweb: the system is responsible for performance. Don’t blame people for doing what the system asks and similarly, stop rewarding individuals for good performance. The system drives performance.

Reward for good performance may be the same as rewarding the weather forecaster for a pleasant day. Deming

I’m utterly convinced (from my experience) that the organisational changes they want will come about when they focus their attention and their energies on the system and not on the individual behaviours of individual people. So when I share my observations with the three of them, they nod and smile and say, “That’s exactly what they’re like; that absolutely describes the culture.”

I then enquire as to what they’ve tried, in order to put a stop to the things they don’t like. Again, I listen for patterns. With all good intentions (for they are really lovely people), they tell me things like:

- “Well, I was going to schedule another one-to-one meeting and go through their KPIs again, but something urgent came up.”

- “I had it written in my diary but I couldn’t remember which page I’d written it on.”

- “I’ve confronted him about it before but it didn’t make a difference, so I couldn’t see the point of following him up again.”

- “He knows what he’s supposed to do, he’s been here for 10 years, I don’t see why I should have to tell him again and again.”

- “They’re like a bunch of children; you have to keep on at them, otherwise nothing gets done.”

- “Yes, I had a chat with him and said I’d meet again a week later to see how he was getting on, but I let it slip.”

- “He was fine for a week after I talked to him, but he’s slipped back and I don’t know how I can get it across.”

After they report what they’ve tried, I ask them to reflect on how similar their patterns are to the patterns they bemoan in the staff: inconsistent, side-tracked etc etc…. Again, they smile. Again they frown. They (fortunately) find it mildly amusing that they are doing much the same as the staff. Here is when I reinforce the idea of systems. They are part of the same system and that very same system will be exerting itself on them. In our conversations, they are becoming more adept at seeing. I mean really seeing.

Remember, Deming said that a system cannot understand itself. It’s not just true because Deming said it. It’s true because it’s true. It doesn’t matter how frustrating we find it, but the systems to which we belong will be exerting their influences on us. We struggle to know this. We struggle to know how much. We find ourselves at times frustrated with ourselves, as well as others. It takes an outside eye, a disinterested party, an objective mirror, to help us to see what we can’t. They’re called blind spots for a reason. Obvious to me, previously hidden to these three leaders, their system is screwy, not the people within it.

These three lovely, well-intentioned leaders have warmed up to the current phase of their work together. Phase two: creating the vision of what you want. Now they are aware of this thing called “culture”, and that it impacts on them and that no one person is to blame for doing what the system urges them to do, they are excited to create a vision for the culture they want. They are beginning to see the wood for the trees and are more able to make connections to the elements within the system that maintain its status quo. They are excited. I ask them naive questions like, “What is your purpose?” “What does your business exist for?” “How would you like it to be here?” and they eagerly discuss things that they feel should be so obvious but when asked directly, need to stop and really think about it.

Lately, rather than see themselves as victims to all those awful things the staff do, they are excited to recast their roles as stewards of the system. They get the paradox of systems thinking: they are in it and subject to it, and at the same time, if they can begin to manage their systems blindness with the help of an outside eye, have the power to do something about it. They are seeing themselves less and less as managers-who-need-to-be-in-control and more as leaders-who-guide-the-culture. They are more infused with hope for the future. The things over which they do have control (policy and procedure manuals, resourcing, their own attitudes, their individual relationships with staff members) are the influencers which they can apply to generate the culture they believe will be more effective and, in the long run, more efficient.

Rather than trying to find new ways to get people to do what they want them to do (re-sharpening their sticks or coating their carrots with glitter), they are thrilled to devote more and more time in our sessions to the thing they want, rather than the multitude of things they don’t. They are thinking bigger: about themselves, about the staff and about the business.

Rather than trying to find new ways to get people to do what they want them to do (re-sharpening their sticks or coating their carrots with glitter), they are thrilled to devote more and more time in our sessions to the thing they want, rather than the multitude of things they don’t. They are thinking bigger: about themselves, about the staff and about the business.

Systems thinking, for me, is not merely an academic exercise. It is real world. It changes lives and workplaces.

Next steps for these three? Well, it’s emergent, a work in progress. We’ve had some ups and downs. We’ve had times when they felt a little like they were banging their heads against a brick wall. At this stage, however, they are hopeful, they are positive and they are now talking more about modelling and leading the change they want to see. (Didn’t some famous peace-loving figure from history say something about that?) They are truly interested in being different themselves. They are considering how to steward a culture of self-responsibility, flexibility and “can do”, learning from mistakes and “just enough” structure….and for me, they are approaching phase three: grappling with the “how-to”.

In truth, it is an absolute pleasure.

when you ask them why their business exists you are just then unveiling the greater system, that even me and you are prisoners of 😉

“businesses exist to sustain the life style of their leaders” – Ackoff

That’s the one Vasco.

I think this article is spot on but the title is misleading. Your article is really saying that it is a behavioural problem, even an individual behavioural problem but that you can’t separate behaviour from the system. You have to look at behaviour as a function of the system. You have to address the whole. Have I misunderstood?

Thanks for commenting Kelly. In my eyes when I’m working with a client such as the one I describe, my starting point is to look at the system. I, myself, don’t classify it as a behavioural problem because in my experience, that locates it in a person. Having said that, I do, as you say, look at behaviour as a function of the system and the solutions come from addressing the whole. I see behaviours as symptoms of something lying deeper within the system than what we see a person doing or not doing.

I totally agree John. When I see behavioural issues or challenges it now makes me curious about the deeper patterns rather than the individual behaviour. When we target the individual, even if their behaviour changes or they leave the team/organization, that behaviour usually pops up somewhere else. When we discover the deeper pattern or what more is going on in the field/system, we can generate a collective shift where individuals all remain valuable to the whole and feel welcome as part of the whole. Nice to come across your writing.

Thanks Kathy. I see similar things to you. Often a system will throw up a need for a particular role and someone fills it. If, as you say, a person’s behaviour changes or they leave, the system will find its scapegoat in someone else. A fascinating functional characteristic of some systems I’ve observed.

John,

In your work to you find that adjusting the system is dependent on behavior changes of individuals?

I agree that the system often drives specific behaviors but ultimately the organization is made up of individuals and the behaviors of the individuals contribute to the culture and the system.

While working on the larger system changes I often find myself adjusting very specific behaviors in individuals to create actual system changes. After all, the system is driven by individuals and small changes in key places can have large impact in complex systems.

True, the system is made up of a bunch of connected and interconnected individuals. It’s one of the fun aspects of this work that if we do something with an individual, there will be ripple effects on those around him or her. In my experience, however, a deeper shift in the system occurs if we work with the system as a whole. Even if we are doing one-to-one work (which is rare in our case) we are taking a systemic approach with a view to individuals making an impact on their wider system. However, the system is greater than a sum of its parts and doing individual work will be limited in effect. I’m also mindful of the 95% rule which is borne out in my experience.

Reblogged this on thinkpurpose and commented:

Woh, good stuff indeed.

Merry Sunday!

This is a really great article. I teach chaos and complexity in business schools, and spend around 1/4 of the modules focussing on seeing, and how our mental models affect our “seeing” so I could really relate to what you are saying here.

Thanks Simon, getting people to understand what a mental model is,…and then to gain some awareness of the ones they see the world through….really essential stuff.

Great post and encouraging for someone who would like to see a system(ic) approach to organizational change. Your explanation of how to work with managers sounds good but when you say ” they are seeing themselves less and less as managers-who-need-to-be-in-control”, my experience is that this is a difficult thing for managers to do.

Because we are dealing with systems issues, these managers have earned their positions (at least in part) by successfully delivering the desirable things that the current system encourages i.e. they are good at being controllers and the system has selected them for that. How reasonable is it to assume that these people will change these deeply entrenched mental models? And yet their ability to change is key. Paradox?

Thanks! …and to my mind the managers you talk about have indeed got where they are by playing to the system’s rules. It is a paradox and takes some work to get people to a place where they are ready to be someone different, if that’s required. It is a challenging thing to do, as you say. If a manager is not interested in transforming their organisation, however, I doubt that I would be in front of them assisting them to open their thinking and shifting their older mental models. People are ready when they are ready and the folks we work with are those who have got to the “I know something different is required, I don’t what that is and I don’t know how to get it” moment. In other words, they actually want to change, they have some personal insight that they need to change themselves, and they are open enough to entertain the fact that their attitudes and beliefs might need examining. This is not work with people who are not ready/willing/able on some level.

Reblogged this on Things I grab, motley collection .

John,

Another stunning post, thank-you. Perhaps the only area I might differ is in the word ‘problem’ itself. To me, the desire to make a change at a business/organisational (system) level is intrinsically linked to those people involved, be they the instigators of the change itself or merely ‘on the receiving end’. I totally agree that the systems in which we operate make a difference to us as individuals and as such can alter our behaviours. The environment, however we bound it, will always have this effect. Whether people’s behaviours are problems or not is, for me, not of interest (it is starting with the supposition that there is something wrong with them that needs fixing and that is very rarely the case) it is all about enabling them to deal with the systems about them whether they are changing or not. This is very much the approach I take when coaching individuals – they aren’t there to be fixed, they are whole beings which includes how they interact with the systems about them.

Now I’ve written that I’m not sure whether I’m disagreeing with you or not, it all seems pretty similar!

All the best

Paul

Thanks Paul…and I think we are on the same page. I don’t like the word “problem” myself; people do what they do and I use a different way of looking at behaviour than as “problematic”. I also don’t see people…or situations…or businesses…as things to be fixed. I suspect I used the word “problem” in my article because people who chat with me talk about their “problem” staff or that so-and-so has a behaviour or attitude problem, which I don’t agree with, but it’s a starting point. That’s why I made that point that seeing things as behavioural problems is out of a mechanistic worldview, which I do believe. Herein sometimes lies the challenge of applying new thinking: we use much the same vocabulary as folks who operate out of old paradigms and so we are often misunderstood (It’s not “Problem 2.0”) or how we synthesise information is seen as a little kooky. I use the word system and many folks I deal with think I’m talking about their “payroll system” or their “IT system” etc etc. I talk about how behaviour is a function of the system and, out of old logic, people assume that if you change behaviour that the system will change. As you know, much more complex than that…..

Reblogged this on Corporate Sensemaker and commented:

As always, John’s words are music to my concepts

Excellent post. I always struggle how to make my colleagues think about the “big picture” without sounding as if I was “evangelizing”.

Reblogged this on Optimizing Healing Healthcare and commented:

Although my studies years ago touched on systems thinking, the more I read, the more I am intrigued about the multitude of ways that systems thinking can make a difference optimizing healing healthcare.

When I was first entering the healthcare industry, one of the strangest things to me was the concept of competition between hospitals and healthcare systems that I observed and felt. A hospital or other healthcare organization’s core mission is to optimize the health of the people they are entrusted to serve and the community in which it is located. Therefore, with multiple hospitals located in a region, it would seem to make sense that shared mission and purpose would be a higher and more noble purpose than competition that pits hospitals one against another.

I’ve learned since that hospitals and health systems are collaborating more and more on a variety of shared challenges: decreasing infections, improving patient safety, etc. And, still, there is still competition that could be better directed at improving the health and wellness of communities served.

In my reading and understanding of John Wenger’s blog “It’s not a behavioural problem: it’s the system” I believe he would advise: “What we need if we want organisational transformation, if we want more effective organisations, if we want people to find the work they do meaningful: we need to work with the whole system.”

I completely agree with Anthony Cirillo who wrote in his most recent About.com blog published today: “Healthcare has to heal itself before it can heal others.” It seems to me that systems thinking is critically important in the process of optimizing healing healthcare.

What do you think?

Hi John

So great to catch up with your blog after a very busy month. One aspect of the dilemmas you articulate so well is failing to pay sufficient attention to the patterns in peoples’ real experiences, those “below the waterline” beliefs, perspectives, feelings and perceptions that are often discounted or discredited. I’d love to hear how you relate the shift toward systemic transformation to those unappreciated (if not fully undiscussable) experiences. Cheers!

Dan, thanks once again for contributing. Those unseen things you mention are all part of the mix, aren’t they? Transformation of any system comes about, in my experience, when at least two processes are attended to: 1) when what is covert becomes overt and 2)when new information enters the system. Whether for an individual trying to transform themselves through therapy or some other kind of personal growth or for a business that is trying to transcend itself, there needs to be an uncovering of the blindspots, the unspoken, the unknown. These things you call “below the waterline” could hinder transformation, so they need to come to the surface. I will add that this is sometimes very gentle work and requires patience: it’s a process (continual learning), not an event (like a harsh performance review). Also, to allow the system to flourish, it must remain open to what is new. New ways of being, new knowledge, new skills, new mindsets, new beliefs, new perceptions.

Hope that comes close to addressing your question.

I appreciate our dialogues!

Cheers

John

Great article John, it remember me a lot of Morpheus chat:”The Matrix is a system, Neo. That system is our enemy. But when you’re inside, you look around, what do you see?” Sometimes it is hard for people to abstract themselves from the day by day to see the underlying culture and shared believes..

Reblogged this on Get "fit for randomness" [with Ontonix UK] and commented:

What we need if we want organisational transformation, if we want more effective organisations, if we want people to find the work they do meaningful: we need to work with the whole system. A buddy of mine in England recently observed that most people seem uninterested in effectiveness. Sad but true, I fear. Still desperately clinging on to “scientific” management mythologies, many folks just seem to want the numbers to add up and people to do what they’re told. A scary prospect if your business has just appointed a new global CEO who is a bean-counter by background and disposition and whose single-minded purpose is to show the shareholders that they are getting richer every quarter. Calling a performance issue a “behavioural problem” comes out of a mechanistic worldview. Yuck.